SWCCF News 2025 03

Felis Nigripes AKA Black Footed Cat

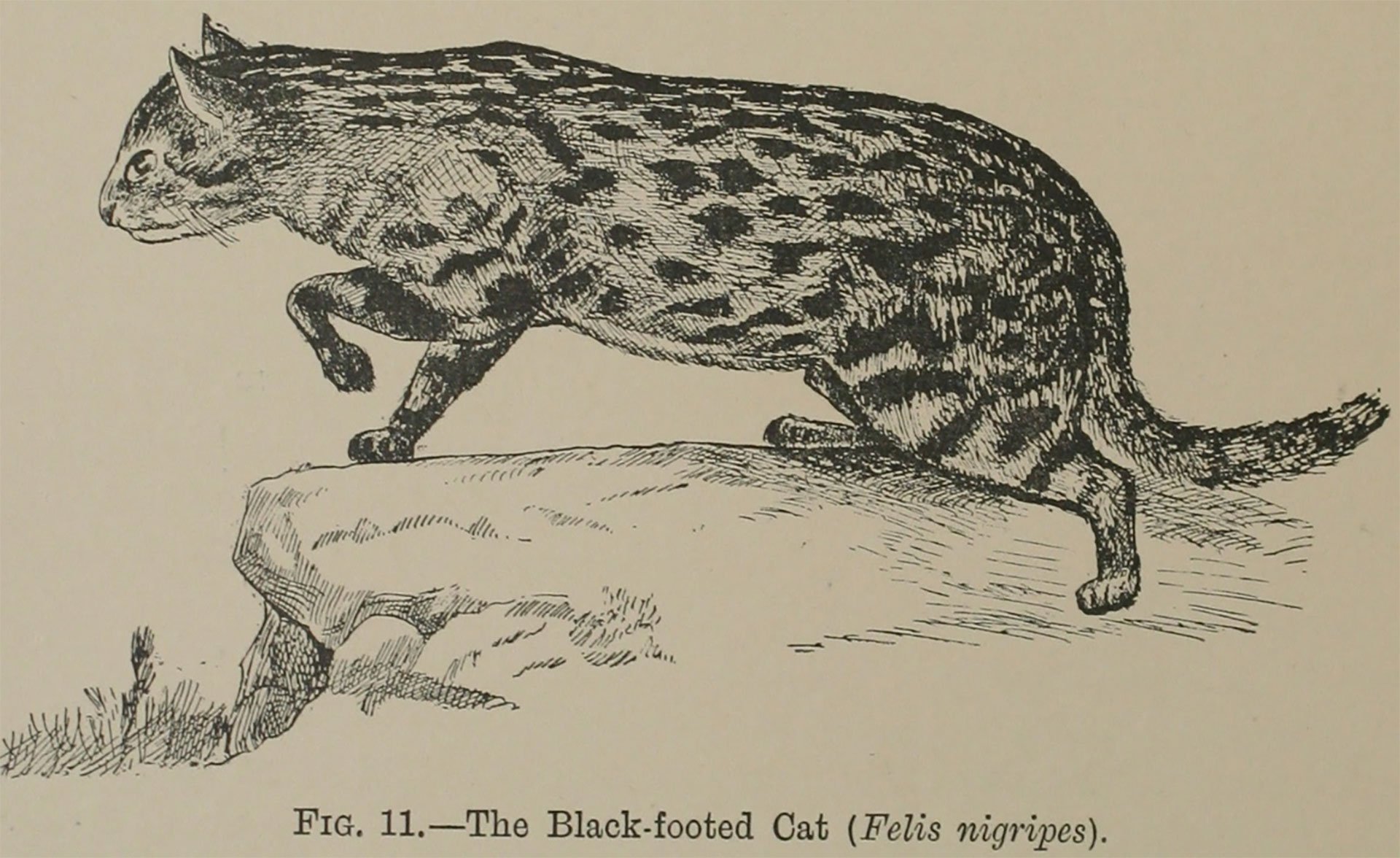

The taxonomic history of the Black-footed cat serves as an example for many small wild cats. William John Burchell described the Black-footed cat in 1824 in the second volume of his two-volume book: Travels in the interior of southern Africa. Burchell's original description amounted to three paragraphs. Though a separate book of illustrations was produced, neither a living individual nor skin of the Black-footed cat (Felis nigripes) was included. Burchell described the cat from 14 skins and likely never saw the living cat that we now know is nocturnal. Without exception, the absence of an illustration of any new small cat species invariably had long-term negative consequences.

Burchell’s failure to illustrate the new species led immediately to doubts of the new species. Unlike Sir William Jardine (1833-43) who included the Black-footed cat as a distinct species but provided no illustration, Saint George Mivart (1892), Richard Lydekker (1893-4 & 1896), and Daniel Giraud Elliot (1878-83) omitted the Black-footed cat in their accounts of the Felidæ. For 76 years, the existence of the Black-footed cat was doubted.

Finally, in 1900 the first illustration of the Black-footed cat (shown above) appeared in William Lutley Sclater’s book The Fauna of South Africa. Sclater’s independent, detailed description and clear illustration of the Black-footed cat convinced naturalists of the cat’s existence, but the natural history of the cat remained unknown. Yet another 75 years would elapse before glimpses of the Black-footed cat's habits would emerge.

Moreover, it goes without writing that if a small cat was described and soon accepted by leading naturalists of the time, then a clear and unmistakable illustration was, without doubt, included in the original first description. Otherwise, acceptance remained in doubt.

The 9th annual Biodiversity Youth Camp 2025 was a huge success! This year’s event was organized by the Save Fishing Cat team in collaboration with Marine Conservation Society and generously supported by the Dilmah Conservation and Sustainability Fund, Rufford Foundation, Fishing Cat Conservation Alliance, and Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation.

Seventy-five students from nine different institutes participated in the three-day program held at a remote location surrounded by serene cloud forest and tea plantation landscapes in the central hills of Sri Lanka. The event started with a 3-km hike to the camp location where our team assisted in preparing the camp site. For three days, everyone participated in nature walks, birding sessions, hands-on experience with field mammals, bird and herpetofauna monitoring methods including the use of trail cameras, capturing and tagging small mammals, and scat and pug mark observations. In addition, informative presentations led by experts on trends in conservation, scientific writing and ethics, introduction to eDNA, how to secure project fundings, the impacts of climate change, marine conservation, and threat reduction programs were also conducted. Lively discussions, often well after dark, were held.

Our program ended with a public event about snakes and myths targeting tea plantation workers and our camp students. This session not only helped dispel common misconceptions about snakes but also taught basic safety measures and species identification, making a real impact on the community.

The goal of our annual Youth Camps is to inspire and recruit new members into our community of passionate young conservationists, equipping them with knowledge, connections, and a deeper understanding of nature no matter what career they choose to follow. If past Youth Camps are an accurate measure of our impact, we anticipate that more than 90% will join our network of action-based conservationists spanning Sri Lanka. As Jim likes to say, the network is the solution.

Cajón del Maipo is a hotspot for wild cats in central Chile where Colocolo, Guigna, Andean cat, and Puma co-occur within just a few kilometers of a small village. The Colocolo Conservation Project visited El Manzano School to carry out environmental education activities and collaborate on a large mural featuring our flagship species. Colocolo Conservation Project volunteers worked with the children who quickly took ownership of the project.

The students and teachers selected both the animals and the wall itself. Colocolo Conservation Project supplied all the materials necessary to complete the project. With great pride, the students and teachers can say the artwork is 100% their own creation. The result is indeed stunning.

Having scaled a chain-link fence and repositioned a ladder, I got a close-up look. I agree with Carlos - quite stunning. JGS.

To celebrate Fishing Cat February 2025, I initiated a door-to-door campaign to assist fish farmers. Our campaign continued throughout February. Our goal was to reach as many active and potential fish farmers as possible, particularly those that had experienced the loss of fish due to Fishing cat predation. Our goal was to fix problems before problems occurred.

On the very first day of our campaign, our team learned from fish farmers themselves what to expect. This unique approach of engaging fish farmers provided us with valuable insights we can use in future campaigns. We are hopeful that this initiative will generate positive momentum and uncover even more crucial information about the Fishing cat and its conservation needs as well as making fishing farmers into our conservation allies.

This March 2025 Small Wild Cat Conservation Foundation newsletter was written and illustrated by Dr. Jim Sanderson